Soaked in history and stories, the prison that was once called the “Spielberg of Irpinia” survives in one of the most beautiful towns in the Campania hinterland: Montefusco.

Ph. Anna Monaco - Trentaremi

Overlooking a splendid and airy valley between Avellino and Benevento, halfway between the Sannio and Irpinia, over the centuries Montefusco has played a crucial role in the administration of justice. In the 15th century, the underground cellars of the castle were used as a judicial prison. Each Principality had one and in Montefusco there was the one of Ultra.

A programmatic note issued by the viceroys of Naples around 1600 suggested that the jails were neither dark nor fetid because they were not intended for punishment but for custody. That of Montefusco was instead dark, humid, underground and so fetid that in summer those who resided in the upper floors of the castle had to go away, so intense was the stench that rose from below.

Ph. Anna Monaco - Trentaremi

But it was in the nineteenth century that the Spielberg of Irpinia consolidated its reputation as a hard prison. When Ferdinand II of Bourbon, worried that the ideas on the unity of Italy advocated by the count of Cavour could spread among the most brilliant minds of his Kingdom, he carried out a ferocious and bloody repression. And the captured political dissidents were taken to the Montefusco prison, in order to make them inoffensive. Besides, what place could have better guaranteed the isolation of the prisoners, if not a small village on the mountain, 700 meters high and far from everything, especially from Naples?

“Chi trase a Montefuscolo e po’ se n’esce po’ dì ca ’n’terra ’n’ata vota nasce”

“Whoever enters Montefusco and then leaves it can say that on Earth he is born again”

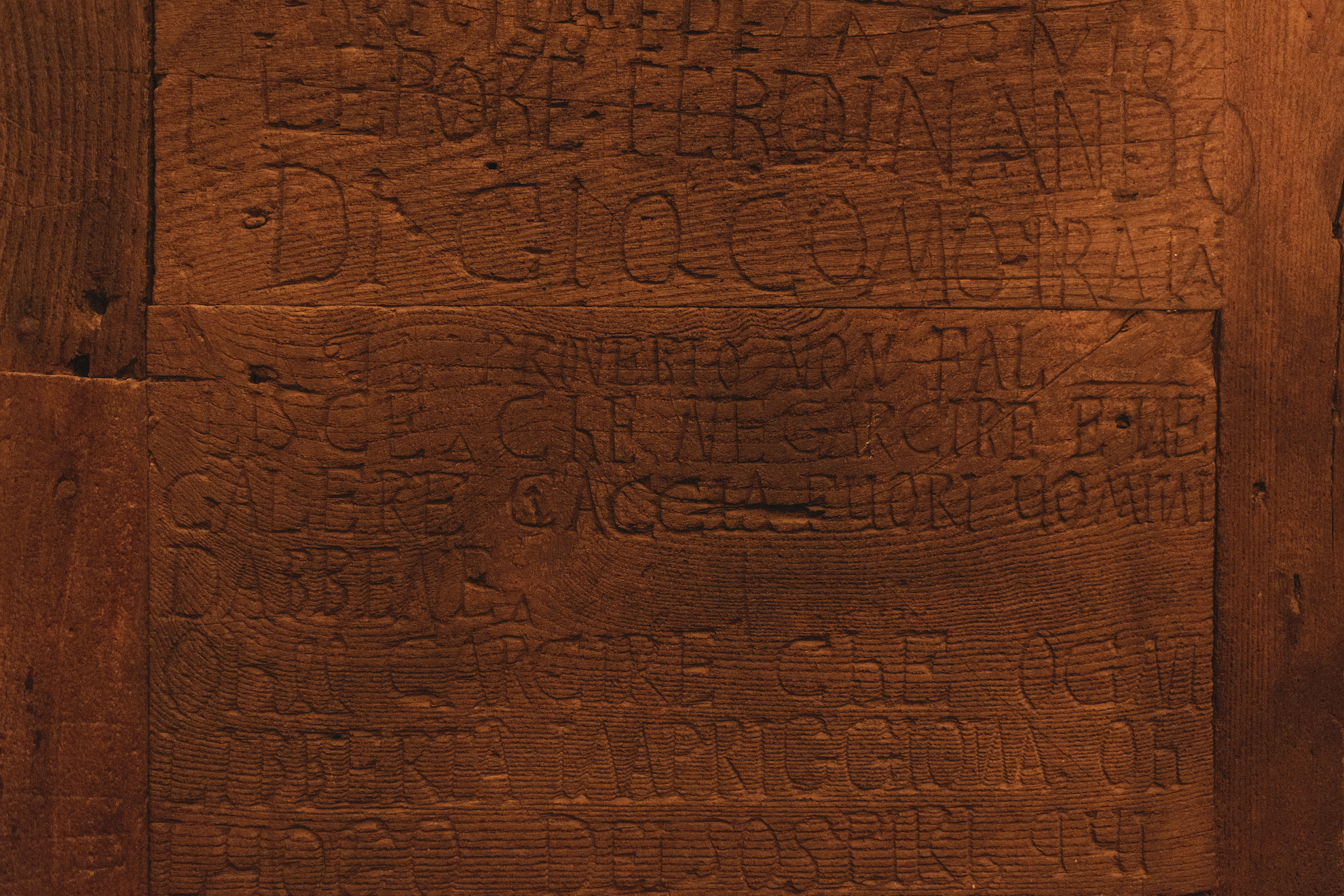

There Cavour's revolutionary and liberal ideas would never have arrived. What kind of penalties the political prisoners suffered within that prison is testified by some phrases found engraved on the walls and today reproduced on the panels that guide us during the visit: “Neither prisons nor galleys educate good people”.

Engravings of prisoners | Ph. Anna Monaco - Trentaremi

Baron Nicola Nisco, Carlo Poerio, former Minister of Ferdinando II, and count Michele Pironti, were detained in Montefusco until 1859, when the life sentence was turned into exile. And they documented the violence and humiliations suffered during detention: daily searches, lack of beds, no hope of privacy, tight spaces, little light, corporal punishment.

Anyone who showed respect or empathy for the poor inmates was first viewed with suspicion and then severely punished. Even a nightingale, who dared to cheer up the days of prisoners with his melodious song, was ruthlessly killed by one of the guards, Duke Sigismondo Castromediano from Lecce wrote in his diaries, as reported by a well documented site dedicated to the history of Montefusco and brigandage.

The parlor of the prison | Ph. Anna Monaco - Trentaremi

Today that place of pain and torture is immersed in the silence of the country and illuminated by warm rays of sun, when the day is good. In 1928 it was declared a national monument and was later renovated, but when you pass the door of that cellar, it is not difficult to imagine how much violence and how many abuses those walls could tell.