Pompeii is a city that speaks with its silences and its apparent immobility. What remains of an ancient civilization risen between the fertile volcanic earth and the sea, before the "sterminator Vesuvius" covered it with ash and red-hot lapilli, still communicates its secrets.

A glass cup with pomegranates frescoed in the Villa of Poppea, in Oplontis | Ph. Anna Monaco - Trentaremi

The first of these is a question that we can finally answer today: when did the eruption occur? When did the explosion of the crater hit, suddenly, the viability of a cosmopolitan city open to the world? The year is clearly known: 79 AD. But what about the day?

Sources that date back to Pliny the Elder and his nephew, Pliny the Younger, report it as happening at end of the summer. On August 24, writes Pliny the Younger in his first letter to Tacitus, his uncle «He was in Miseno and, presently, he was ruling the fleet. August 24th was just an hour after noon and my mother showed him a cloud that appeared, never seen before in size and shape. [...] The cloud rose, we did not know with certainty from which mountain, since we looked from afar; only later did it become known that the mountain was Vesuvius».

Everything solved? Perhaps not. Precisely because Pompeii is a city that is never silent, the research and excavations carried out over the last century have highlighted some details that perhaps do not align with the story that Pliny the Younger tells us. Or, at least, with what has been handed down to us by medieval scribes who copied ancient texts.

Charred nuts found in Moregine, close to Pompeii | Ph. Anna Monaco - Trentaremi

Two elements: the finding of some types of fruit and an inscription, present in the Garden House, still today closed to the public and studied.

We are in the last years of the nineteenth century. Pompeii is an open-air construction site. The Bourbon Royal family understands that this immense city submerged in the earth is an unrepeatable opportunity to see their prestige as rulers increased, even in other European courts. Who else, moreover, can boast a similar archaeological treasure dating back to ancient Rome (if not before?). The excavation operations therefore proceed steadily and laboriously. Until the remains of some fruits are found. They too are perfectly preserved and distinguishable from one another.

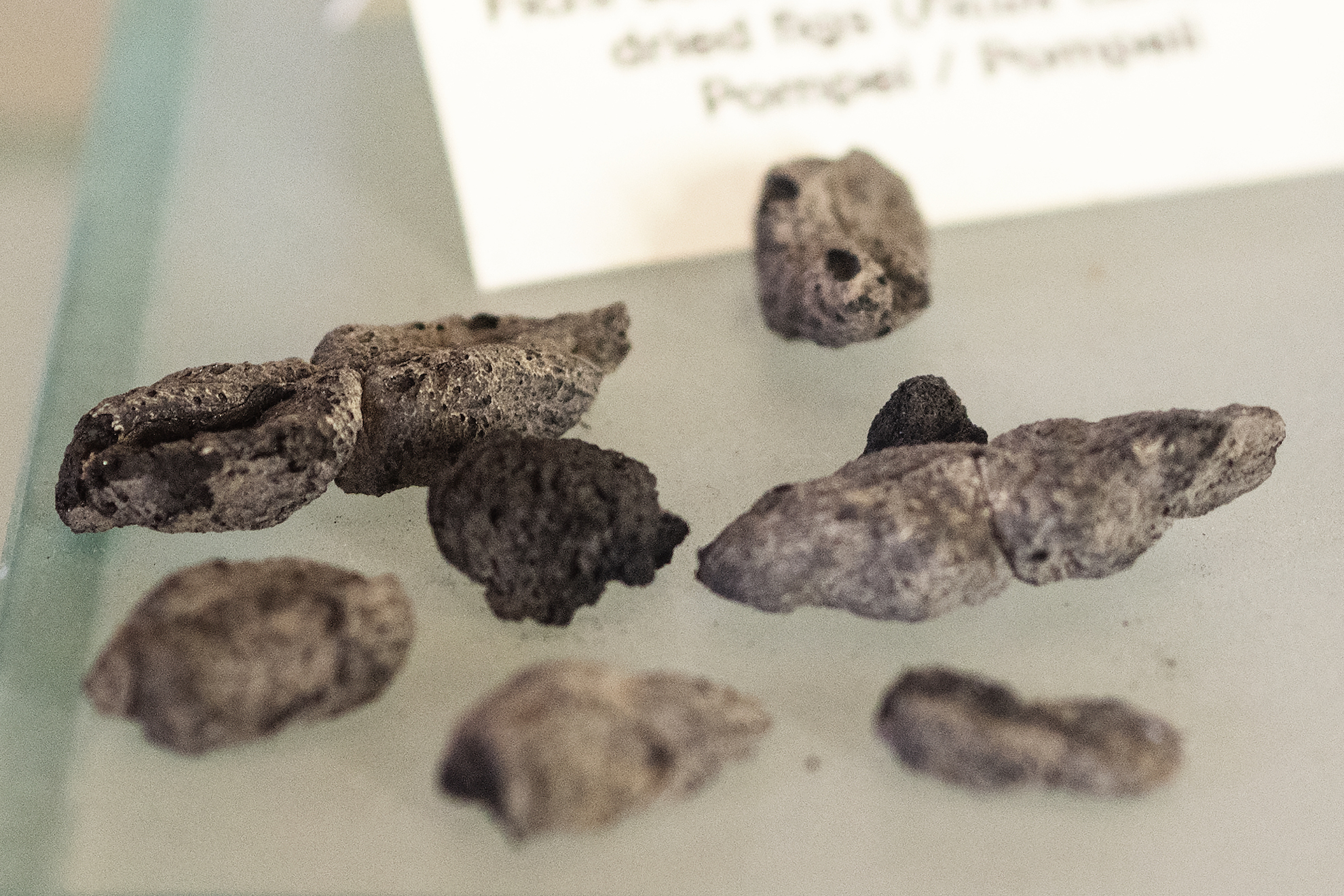

First of all, bunches of grapes, round and perfectly ripe, probably ready for harvest. Next to them, various kinds of fruit: pomegranates, walnuts, dried figs and even almonds. Findings that lead us to think, yes we are talking about fruit that is present in August (like grapes and figs) but these had reached a state of maturation that makes us presume that their presence on the tables means that it was autumn, and not full summer.

Almonds preserved in the Antiquarium of Boscoreale | Ph. Anna Monaco - Trentaremi

From this clue it was decided to reformulate the date of the eruption: not August, but a month compatible with the findings. A month in which the harvest had already taken place and the fruits were already available for the Pompeian population: thus evolves the hypothesis that the month of the tragedy was October.

We thus arrive at the inscription. Which, in addition to the month, helps us define even the day. It is on a wall of the Garden House, as already mentioned, that in October 2018 a charcoal-engraved phrase is found, "which could be the work of a jolly worker who wrote it on the wall of a room under renovation", says the general director of the excavations, Massimo Osanna.

Paired dried figs found in Pompeii | Ph. Anna Monaco - Trentaremi

What is important for establishing the date is not so much the meaning of the sentence, not yet deciphered, but two elements: a date and the material used. The first is easy to detect: below the sentence is the day of its inscription, that is, the "sixteenth day before the calends of November". In practice: our 17th of October. And who is to say that that sentence had not been engraved a few years before, instead of the fateful 79?

The material, in fact. Charcoal, in fact, is fragile in itself: it cannot withstand many days in the open air. That inscription, in all probability, only had a few days of age before Vesuvius stopped it in time along with everything else around it.